Bonnie and Clyde

In 1931 West Dallas, Bonnie Parker finds Clyde Barrow attempting to steal her mother’s car. Rather than being alarmed, she’s intrigued by his dangerous edge. When Clyde reveals his prison time and shows off his gun (subtlety isn’t his strong suit), Bonnie is captivated. He seals the deal by robbing a store just to impress her, and suddenly this small-town waitress sees her ticket out of a life of serving coffee and settling for mediocrity.

Their early crime spree is more comedy than criminal masterstroke. Clyde’s first attempt at a bank robbery goes sideways when there’s no money in the bank – turns out the Depression hit everyone hard. They start small, knocking over grocery stores and gas stations, with Clyde fumbling his way through hold-ups while Bonnie cheers from their stolen getaway cars. There’s a particularly telling scene where Clyde can’t even park properly during a robbery, much less shoot straight.

The Barrow Gang really takes shape when they pick up C.W. Moss, a gas station attendant who knows cars better than he knows common sense. Then comes Clyde’s brother Buck, fresh out of prison himself, with his wife Blanche, a preacher’s daughter who’s about as suited for crime as a penguin is for the Sahara. Her constant hysteria provides an interesting counterpoint to Bonnie’s cool-as-a-cucumber approach to their lifestyle.

The film delves into some fascinating character dynamics, particularly around Clyde’s impotence (both literal and metaphorical – the film’s not exactly subtle about this symbolism). Bonnie’s frustration with their physical relationship leads to one of the most intimate scenes in the movie – and it involves a Coca-Cola bottle, of all things.

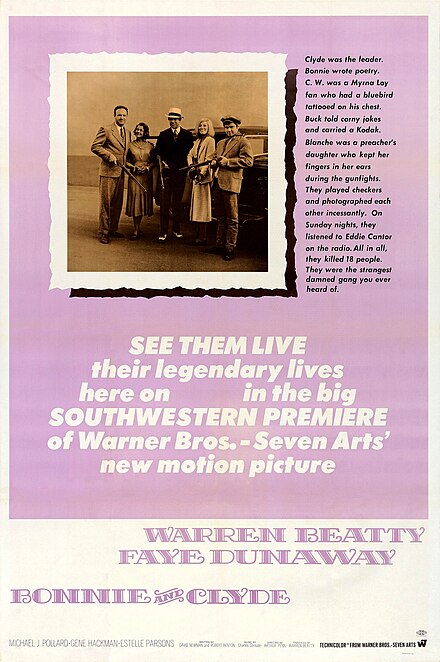

Their rise to fame is meticulously detailed. They take photos like celebrities, with Bonnie hamming it up with a cigar and gun, creating iconic images that would make their way into newspapers across the country. They even have a brief encounter with a farmer whose house has been repossessed by the bank – a scene that positions them as Robin Hood figures, even though their robberies were more self-serving than philanthropic.

The violence escalates gradually but significantly. What starts as warning shots turns into casualties, with each death hardening them a little more. There’s a particularly brutal scene where they kidnap a young cop, share laughs with him, then have to kill him – a moment that shows how far they’ve fallen from their early romantic notions of being outlaws.

The beginning of the end comes at their hideout in Joplin, Missouri. A shootout with the police leaves two officers dead, but they escape with rolls of film that would later become famous photos of their gang. However, their luck starts running thin. A subsequent shootout at a motor court proves catastrophic – Buck takes a bullet to the head but doesn’t die immediately, leading to scenes of Blanche’s devastating breakdown as she watches her husband slowly slip away.

The final act is set in motion by C.W.’s father, Malcolm Moss, who makes a deal with the authorities. The ambush is meticulously planned by Frank Hamer and his team, who wait by the side of a rural road in Louisiana. The famous ending sequence shows Bonnie and Clyde sharing a look – a moment of unspoken understanding – before their car is riddled with enough bullets to make Swiss cheese jealous. Director Arthur Penn films their deaths in a balletic slow motion that somehow manages to be both brutal and beautiful.

Throughout the film, there’s a recurring theme of Bonnie’s desire for fame and recognition. She writes poetry about their exploits, ensures their stories make the papers, and seems more concerned with how history will remember them than with the morality of their actions. In a darkly ironic twist, she gets her wish – just not quite in the way she imagined.

The film also weaves in subtle commentary about the media’s role in creating celebrities out of criminals, the economic desperation of the Depression era, and the death of the American frontier spirit – all themes that resonate surprisingly well even today. Though at its heart, it remains a story about two kids playing at being outlaws until the game becomes all too real.

★★★☆☆ “Bonnie and Clyde” revolutionized American cinema with its bold blend of violence and romance, even if some of its performances now feel as theatrical as a high school production of “Romeo and Juliet.” Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway attack their roles with the subtlety of a tommy gun, chewing through scenes with wild-eyed abandon that occasionally threatens to overshadow the film’s groundbreaking narrative. Gene Hackman provides a more measured performance as Buck, though Estelle Parsons as Blanche seems determined to shatter every window in Texas with her piercing screams. Yet despite these melodramatic tendencies, the film’s importance cannot be overstated – it helped usher in New Hollywood with its frank depiction of violence, sexuality, and moral ambiguity, while its influential editing techniques and unflinching finale remain powerful even today. The story of these Depression-era outlaws may be heightened by its performances, but its examination of celebrity culture, violence, and American mythology laid the groundwork for countless films to follow, making it an essential piece of cinema history, even if you occasionally need to turn down the volume.