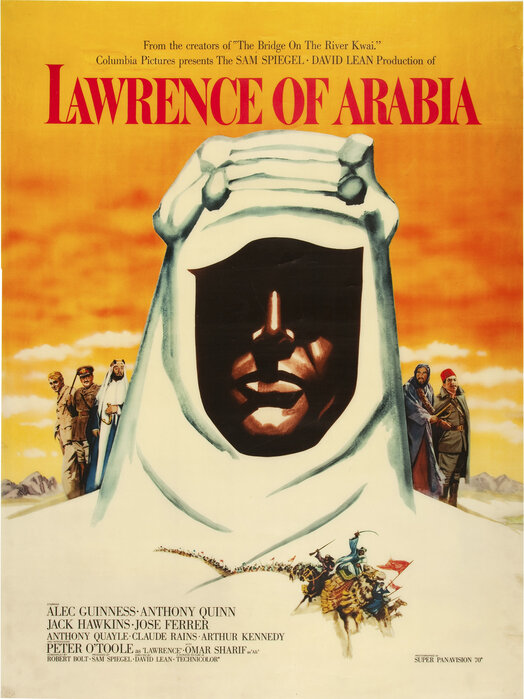

Lawrence of Arabia

Let me take you through this monumental epic, which manages to feel both impossibly vast and deeply personal at the same time.

The story begins with Lawrence’s death in a motorcycle accident (ironically, after surviving all his desert adventures), before rewinding to show us the eccentric British Army lieutenant in Cairo, where his insubordinate attitude and scholarly interests make him stick out like a sore thumb in the military bureaucracy. When he’s assigned as a liaison to the Arab Bureau, it’s partly because his superiors just want him out of their hair – though this “punishment” ends up changing the course of history.

The film really hits its stride when Lawrence meets Prince Feisal (Alec Guinness, doing his best with a role that really should have gone to an Arab actor). Here we get our first glimpse of Lawrence’s growing infatuation with Arab culture and his emerging messiah complex. His first major achievement – crossing the “uncrossable” Nefud Desert to attack Aqaba from the unprotected landward side – establishes his reputation for achieving the impossible. The scene where he returns alone into the desert to rescue a lost man perfectly encapsulates his character: equal parts messiah, madman, and military genius.

The film takes a darker turn after Lawrence’s capture in Daraa. The sequence where he’s “entertained” by the Turkish Bey (though the film leaves the specifics of his torture and possible sexual assault ambiguous) marks a crucial turning point. O’Toole’s performance becomes increasingly unhinged after this – his eyes take on a wild gleam, and his actions become more brutal. The massacre of the Turkish column at Tafas, where Lawrence orders “no prisoners,” shows just how far he’s fallen from the idealistic officer we met in Cairo.

What makes the film particularly fascinating is how it refuses to either fully condemn or celebrate Lawrence. Was he a liberator or another kind of colonizer? A friend to the Arab people or someone playing at being Arab? The film suggests all these things might be true simultaneously. There’s a brilliant scene where Lawrence stares at his reflection in a dagger’s blade, seemingly unsure of who he’s become – it’s worth the price of admission alone.

The political machinations in the background are equally compelling. While Lawrence is leading his Arab army to victory, the British and French are already carving up the Middle East in the Sykes-Picot Agreement. There’s a devastating moment when Lawrence realizes his promises of Arab independence were hollow – he was just another tool of colonial policy, despite his genuine belief in the Arab cause.

The film’s technical achievements are staggering. Consider the famous cut from Lawrence blowing out a match to the rising desert sun – it’s taught in every film school for a reason. The battle sequences are enormous in scale (no CGI armies here – those are thousands of real extras), yet Lean never loses sight of the human drama. The scene where Lawrence walks atop a captured Turkish train, soaking in the adulation of his men, tells us everything about his psychological state without a word of dialogue.

Special mention has to go to the supporting cast. Omar Sharif’s Sherif Ali transforms from would-be assassin to Lawrence’s closest friend and voice of reason. Anthony Quinn’s Auda abu Tayi steals every scene he’s in, bringing a magnificent swagger to the Bedouin chief who fights “because it is my pleasure.” Even smaller roles, like Claude Rains as the craftily pragmatic Mr. Dryden, add depth to the political intrigue.

The film’s handling of Lawrence’s sexuality and gender expression was remarkably ahead of its time, even if it couldn’t be explicit about it. His famous line “The trick is not minding that it hurts” takes on multiple meanings, and his delight in wearing Arab robes speaks to someone finding freedom in a different cultural identity.

Most impressively, “Lawrence of Arabia” manages to be both a celebration and critique of the heroic narrative. It shows us Lawrence’s achievements in all their glory while simultaneously questioning the very nature of Western intervention in the Middle East – questions that remain painfully relevant today. By the end, when Lawrence returns to England in his British uniform, looking uncomfortable and out of place, we understand that he’s a man who belongs nowhere – too Arab for England, too English for Arabia, and perhaps too mythologized to ever be truly understood.

The film’s nearly four-hour runtime might seem daunting, but like the desert itself, it operates on its own sense of time. This is cinema at its most ambitious and accomplished – a character study painted on the largest possible canvas, where the spectacular desert vistas serve as both backdrop and mirror to Lawrence’s internal journey. It’s a reminder of what movies can achieve when they aim for true greatness.

★★★★★ David Lean’s sweeping masterpiece “Lawrence of Arabia” swallows you whole like the endless sea of sand that serves as its majestic backdrop. Peter O’Toole, in his career-defining role, brings T.E. Lawrence to life with a hypnotic intensity that borders on feverish – watching his transformation from prissy British officer to messianic desert warrior feels like witnessing someone slowly lose their grip on sanity under the merciless Arabian sun. The supporting cast is a feast of powerhouse performances, with Omar Sharif’s dignified Sherif Ali and Anthony Quinn’s thunderous Auda abu Tayi practically vibrating with barely contained energy. Yes, this epic runs longer than a camel can go without water (216 glorious minutes), but every frame of Freddie Young’s cinematography is a painting come to life, from shimmering mirages to the most famous match cut in cinema history. Maurice Jarre’s sweeping score doesn’t so much accompany the film as possess it. While modern viewers might raise an eyebrow at white actors playing Arab roles (a problematic Hollywood tradition that persisted far too long), the film’s exploration of colonialism, identity, and the price of greatness remains startlingly relevant. Lean’s direction transforms what could have been a stuffy biographical film into a psychological odyssey that’s both intimate character study and grand spectacle. Like the desert itself, “Lawrence of Arabia” seems to exist outside of time – massive, mesmerizing, and absolutely essential.