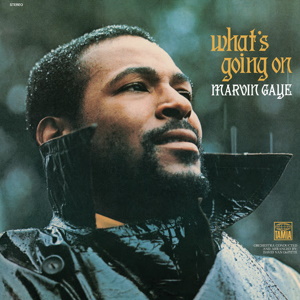

Marvin Gaye – What’s Going On?

f the 1900s produced a single album that defined not just a moment, not just a movement, but the entire human condition, it’s What’s Going On. This isn’t just Marvin Gaye’s masterpiece—it’s the masterpiece. It’s the album that took soul, R&B, and protest music and wove them together so seamlessly, so beautifully, that you almost forget it was born out of pure heartbreak and rage. It’s the most important album of its time, and the most hauntingly relevant album of ours.

Before What’s Going On, Marvin Gaye was Motown royalty—the voice behind silky, romantic hits like “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” and “I Heard It Through the Grapevine.” But by 1971, he wasn’t in the mood for love songs. His brother had just come back from Vietnam, traumatized. The country was in turmoil—civil rights protests, police brutality, poverty, an endless war overseas. And Marvin himself was in crisis, mourning the death of Tammi Terrell and questioning everything, from his music to his faith to the very country he called home. Instead of giving the world another Motown hit, he gave them this: an album that asked the hardest, simplest question of all—what’s going on?

It starts with the title track, and from the first notes, you realize this isn’t just a song—it’s a spiritual awakening. Those saxophones don’t just play, they breathe. The layered, conversational vocals sound like ghosts speaking from another dimension. Marvin’s voice is smooth, pleading, aching as he delivers the line that still echoes half a century later: “You know we’ve got to find a way, to bring some lovin’ here today.” It’s not just a protest song—it’s a prayer.

Then comes “What’s Happening Brother,” a song so intimate it feels like a letter home from war. It’s about Marvin’s brother, yes, but it’s also about every soldier, every displaced person, every lost soul trying to find their way back to a country that no longer feels like home. And just when you think the album can’t get heavier, “Flyin’ High (In the Friendly Sky)” slides in, a devastating, jazz-soaked meditation on addiction, delivered so delicately that it almost feels like floating—until you realize it’s really about falling.

The genius of What’s Going On is that it never stops moving. The songs flow into one another, seamlessly, like a single unbroken thought. “Save the Children” is a desperate cry for the future, “God Is Love” is a hymn disguised as a groove, and then we hit the track—“Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology).” Who else, in 1971, was making environmental protest music and making it sound this good? It’s as smooth as silk but as urgent as a siren, and the fact that it still applies today, maybe even more than it did then, is either proof of its timeless brilliance or an indictment of everything we’ve failed to fix.

And then there’s “Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler),” the album’s haunting, gut-punch of a finale. It’s not just a song—it’s an entire system breaking down in real time. Marvin lays it all bare: crime, poverty, war, systemic injustice. And yet, the groove is hypnotic. He’s telling us the truth, but he’s making sure we feel it. When that final, ghostly reprise of “What’s Going On” fades out, it feels less like the end of an album and more like a warning: this isn’t over.

Culturally, What’s Going On didn’t just shake the world—it changed it. It forced Motown to grow up. It paved the way for artists like Stevie Wonder, Curtis Mayfield, and Prince to be as socially conscious as they were musically innovative. It made soul music deeper, richer, more urgent. And five decades later, it still stands as the single greatest artistic statement ever made about America’s struggles—because tragically, so many of those struggles still exist.

There are albums that define genres. There are albums that define generations. And then there’s What’s Going On—the album that defines humanity itself. It’s the pinnacle of the 20th century, not because of its influence (though that’s undeniable), not because of its sonic brilliance (though it’s flawless), but because it speaks to something bigger than music. It’s the album that asks the right questions, the album that dares to care, the album that never stops being true.

And if we’re still asking what’s going on in the 21st century, maybe it’s because we still need to listen.