The Pianist

Roman Polanski’s The Pianist is one of those movies that doesn’t just tell a story—it makes you live inside it, smothering you in a slow, methodical descent into hell. If you came looking for a standard World War II drama with sweeping battle scenes, a rousing musical score, and an obligatory moment where someone nobly sacrifices themselves while looking up at the sky, then congratulations—you are in the wrong place. This isn’t a movie about war, heroism, or resistance fighters saving the day. This is about survival, and survival isn’t glorious. It’s humiliating. It’s degrading. It’s watching the world collapse around you while you slowly wither away in the corner, praying no one notices you exist.

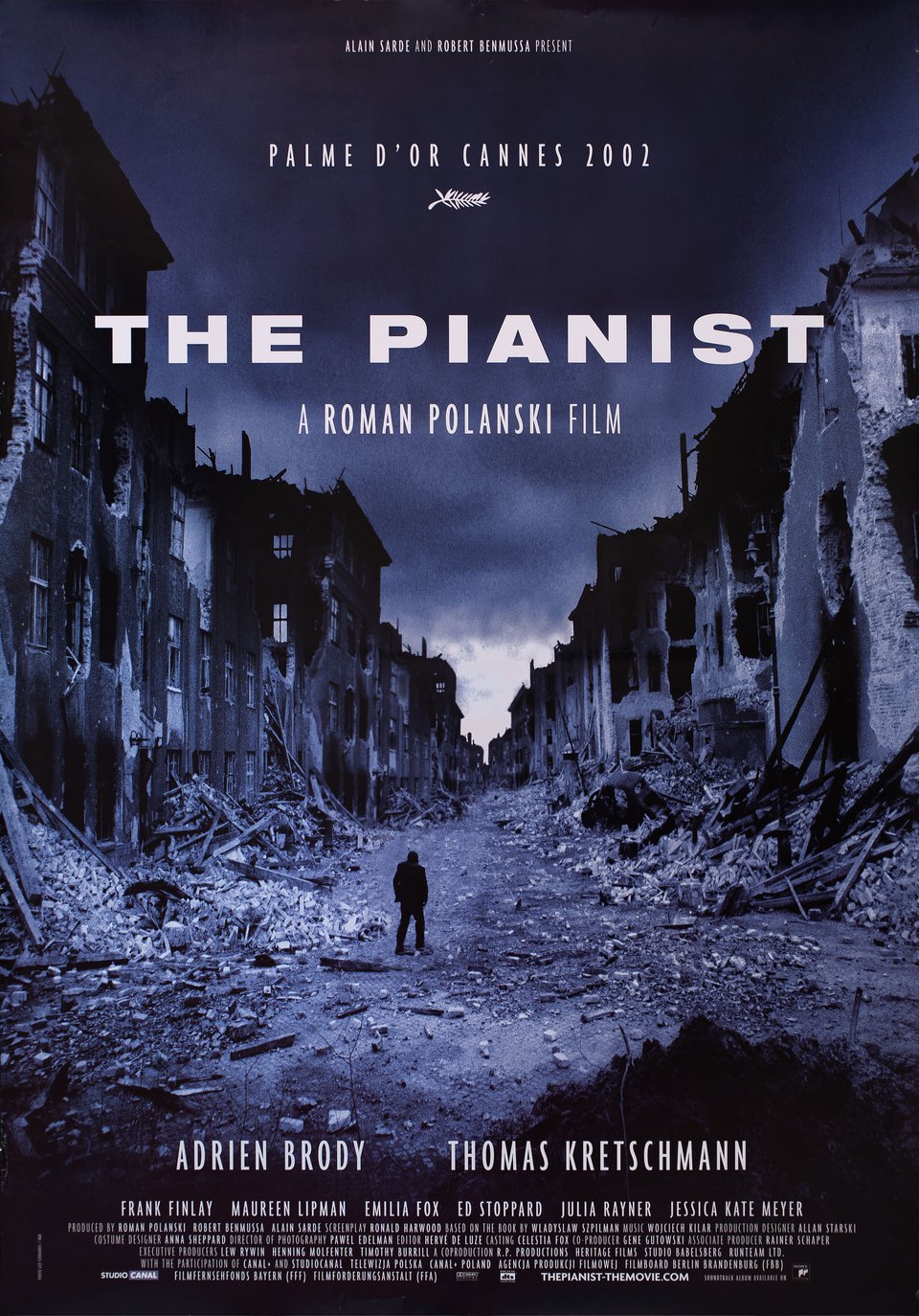

Adrien Brody plays Władysław Szpilman, a Polish-Jewish pianist who starts the movie playing Chopin in a Warsaw radio station and ends it looking like a half-dead scarecrow wandering the ruins of civilization. At the beginning, he’s got everything—family, talent, a home, a nice suit. But as the Nazis tighten their grip on Warsaw, all of it gets stripped away, piece by piece, until all that’s left is a man too weak to stand, hiding in the debris like a ghost who hasn’t realized he’s dead yet. Brody is phenomenal here, and not just in the way he physically transforms from a well-fed, confident musician into a skeletal shell of himself. He barely speaks for half the movie, yet you can feel every ounce of his suffering through his eyes. He doesn’t play Szpilman as a grand, defiant survivor—he plays him as a man who keeps existing simply because he has no other choice.

And let’s talk about Polanski’s direction, because it’s surgical in the way it destroys you. The film never indulges in melodrama, never turns Szpilman into some kind of cinematic martyr. Instead, it just follows him, unflinchingly, as he endures horror after horror. One moment, he’s playing music at a party. The next, he’s watching an old man in a wheelchair get thrown off a balcony by German soldiers. A few scenes later, he’s watching his family get herded onto a train, and he knows—without a word being said—that he will never see them again. The violence here isn’t stylized, it isn’t dramatic, it’s just cold, brutal, and matter-of-fact. People are shot in the street like it’s nothing. Families disappear overnight. The world goes mad, and Szpilman can do nothing but drift through it, clutching his hunger and his silence.

By the time we reach the last act of the film, Szpilman has been reduced to a walking corpse, hiding in the ruins of Warsaw, scrounging for scraps like a stray dog. And then, in one of the most quietly devastating scenes in war movie history, he is finally discovered—by a German officer, no less. And what does he do? He plays the piano. He sits at that broken, dust-covered instrument and plays as if the world isn’t burning outside. And somehow, for just a moment, music, the very thing that defines him, becomes his salvation. Because in a world that has taken everything from him—his family, his dignity, his home—his ability to create something beautiful is the only thing he has left.

The Pianist is not an easy watch. It’s not meant to be. It’s the kind of film that leaves you sitting in stunned silence when the credits roll, the kind that makes you feel like you’ve lived through something rather than just watched it. It doesn’t ask for your tears, but it takes them anyway. It’s a masterpiece, yes, but in the most haunting way possible—the kind of masterpiece that lingers in your bones long after the screen goes black.