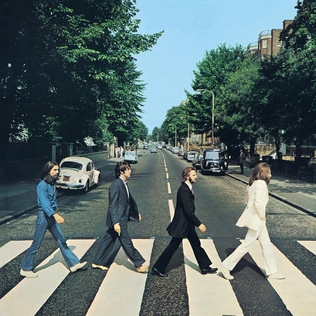

The Beatles – Abbey Road

here are great albums, and then there is Abbey Road, which doesn’t just sit at the top of the mountain—it built the mountain, paved the road up it, and then casually walked across a zebra crossing on its way out. Released in 1969 as the Beatles’ last recorded album (yes, Let It Be technically came later, but let’s all agree to pretend that never happened in this timeline), Abbey Road is the sound of four geniuses who barely tolerate each other making some of the best music of their lives. It’s both a swan song and a defiant middle finger to anyone who thought they’d lost their touch, and if it weren’t for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band hogging all the nostalgic glory, this would be the definitive Beatles album. Scratch that—maybe it is.

From the opening bass line of “Come Together,” where Paul McCartney’s groove is so thick you could spread it on toast, to the farewell whisper of “The End,” Abbey Road is a masterclass in reinvention. “Come Together” itself is a bluesy, slinky number that sounds like it was born in a smoky bar in a dream. It makes no lyrical sense whatsoever, but it’s so cool you don’t care. Then there’s “Something,” where George Harrison decides he’s had enough of being the quiet one and writes the greatest love song in the Beatles’ catalog, making Sinatra gush about how it was the best love song ever written (which is hilarious, considering he also thought it was a Lennon/McCartney tune).

McCartney, never one to be outshined, serves up “Oh! Darling,” a song where he howls like he’s been time-traveling with Little Richard, and “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer,” a whimsical little murder ditty that sounds like a children’s song if that child were a sociopath. Then there’s “Octopus’s Garden,” which is probably the only time anyone has ever been grateful for Ringo singing lead. It’s charming, it’s goofy, and somehow, it works—mostly because George Martin’s production is so pristine it could make an actual octopus cry tears of joy.

But let’s be honest, Abbey Road is really about that Side B medley, where McCartney, Lennon, and George decide to stop writing full songs and instead create a sprawling, perfectly stitched-together rock opera in miniature. “You Never Give Me Your Money” starts as a gentle lament before it becomes a carnival of rock and roll, “She Came In Through the Bathroom Window” is a cryptic fever dream that sounds way cooler than its story actually is, and by the time we hit “Golden Slumbers,” McCartney is singing like a man who knows this is the end of something historic. And then there’s “The End” itself, where Ringo finally gets his drum solo (a tasteful one, no less), and the three guitarists engage in an unprecedented six-string duel, before the Beatles bow out with the immortal words: “And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.” It’s almost unbearably poetic.

If Abbey Road were just a collection of songs, that would be one thing, but its cultural impact is immeasurable. That album cover alone—four men casually crossing the street—has been parodied, imitated, and worshiped to the point where tourists still risk getting flattened by London traffic just to recreate it. Sonically, it was groundbreaking, from its pioneering use of the Moog synthesizer to its meticulous production that set the gold standard for album recordings moving forward. Every major rock band in the ‘70s took notes from Abbey Road—Queen, Pink Floyd, even Zeppelin leaned into the idea that a rock album could be a fully realized piece of art rather than just a collection of singles.

So why is Abbey Road a top-five album of all time? Because it’s not just an album—it’s a myth. It’s the sound of the greatest band ever finding one last spark of unity before the inevitable implosion, of four men who changed the world choosing to go out not with a whimper, but with a masterpiece. It’s proof that music doesn’t just reflect culture—it creates it. And if we’re being honest, Abbey Road is so damn good, it almost makes you forget about Let It Be. Almost.