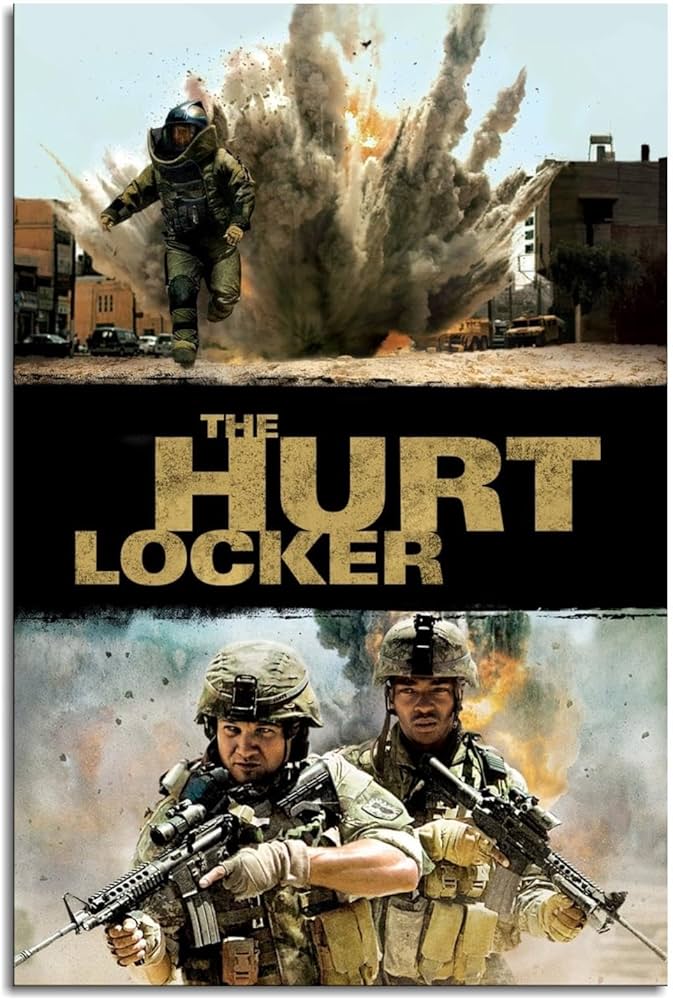

The Hurt Locker

Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker isn’t just a war movie—it’s a 131-minute stress test for your central nervous system. This isn’t one of those big, sweeping, patriotic spectacles where war is just a backdrop for heroism, camaraderie, and some dude writing sentimental letters home while soft orchestral music swells. No, this is war as pure, undiluted anxiety. This is war as an abusive relationship between a man and a bomb suit. This is war where every trash bag, abandoned car, and suspiciously placed goat could be the last thing you ever see. And the best part? You get to spend all of it inside the increasingly unhinged mind of Staff Sergeant William James, played with reckless brilliance by Jeremy Renner.

Renner’s James is not your typical movie soldier. He’s not here to brood about the morality of war or deliver grand monologues about duty and sacrifice. No, this man treats bomb disposal the way a daredevil treats BASE jumping, except instead of a parachute, he has a pair of wire cutters and a questionable amount of impulse control. He’s the guy who looks at a bomb that could level a city block and thinks, “I wonder how close I can get before this thing turns me into confetti.” He sweats adrenaline, makes every safety protocol weep, and approaches each explosive like it just insulted his mother. The man is addicted to war, which the movie kindly reminds us is “a drug.” Yeah, no kidding.

And while James is out here treating life like a Call of Duty lobby, his team—played by Anthony Mackie and Brian Geraghty—spends most of the movie vacillating between barely concealed terror and wanting to punch him in the face. Mackie’s Sanborn is the no-nonsense professional who, shockingly, does not appreciate James’ bomb-defusing-by-vibes-only approach. Meanwhile, Geraghty’s Eldridge is the poor guy who looks like he wandered into this war zone by accident and now can’t figure out how to leave. Their dynamic is basically “daredevil maniac and the two exhausted guys who have to keep him from dying,” which would be hilarious if it weren’t also completely terrifying.

But what really makes The Hurt Locker stand out isn’t just the tension—it’s how relentlessly it drags you into the chaos. Bigelow’s direction makes you feel like you’re right there in the dirt, sweating through your shirt, wondering if the old man watching you from a rooftop is just a guy enjoying the sunset or someone about to set off an IED with his Nokia brick phone. The handheld camerawork, the rapid cuts, the eerie silence that hangs in the air right before everything goes to hell—it all adds up to a film that doesn’t just depict war; it immerses you in it.

And yet, for all its high-octane suspense, The Hurt Locker isn’t about action—it’s about obsession. It’s about how, for some people, the war never really ends, even when they leave the battlefield. James might be able to dismantle bombs with his bare hands, but he can’t dismantle the part of himself that craves the rush. There’s a moment near the end where he stands in a grocery store aisle, staring blankly at an endless row of cereal boxes, completely lost. The choices are overwhelming. The stakes are non-existent. There’s no life-or-death tension, no adrenaline, no purpose. He looks more afraid in that moment than he does when he’s facing down a car bomb. Because the truth is, war is the only place he truly feels alive.

So yeah, The Hurt Locker is a masterpiece, but it’s the kind of masterpiece that leaves you slightly nauseous, vaguely anxious, and questioning whether you should have watched something with talking animals instead. It’s a film that doesn’t glorify war, but it does understand the terrifying allure of it. It grabs you by the collar, drags you into the dirt, and doesn’t let go until you’re just as rattled as the men on screen. And if you somehow make it through the whole thing without stress-eating an entire bag of chips, congratulations—you’re either a robot or William James himself.